All about Ricotta

Mild, delicate ricotta adds a creamy layer to lasagna, makes a fluffy filling for cannoli, and can be a rich topping for artisanal pizzas. It’s versatile and easy to find. You can even make it at home. But while all ricottas might carry the same name, the cheeses you find in the market can vary substantially in texture and flavor.

What is Ricotta?

Liam making ricotta

The process for making ricotta is both simple and unique. While most types of cheese are made with whole milk, ricotta is traditionally made by re-cooking the whey that is left over from making those other cheeses. Here’s how the process works: When you make a regular cheese, you’re curdling the milk with rennet—an enzyme that changes the proteins and allows them to separate from the whey. Those curds are made of the casein proteins in the milk. At this stage, the whey proteins are still stuck in the whey, because they’re water-soluble. If you heat the whey, however, and the acidity is right, you can destabilize the whey proteins until they come out of solution. Scoop out those proteins, and you have ricotta. (The process is actually right in the name: The word ricotta means “re-cooked” in Italian.)

“Ricotta started as something that was made as an additional revenue source and an additional food source for subsistence farmers,” says Liam Callahan, the owner and cheesemaker at Bellwether Farms in Sonoma County, California. But as the cheese became more popular, producers (in Italy and abroad) began making this style of cheese with whole milk as well, to satisfy the demand. Today, you can find ricotta made with whey (which is sometimes called “ricottone”), but it’s usually mixed with a bit of whole milk or cream to boost the fat content and give the cheese more body and a creamier texture. You can also find ricottas made from whole or skim milk, or, often something in between. (The term “whole milk ricotta” covers any cheese made with at least 8% fat, not just cheese made from actual whole milk.)

Types of Ricotta—and Their Uses

Most ricottas sold in the US fall into two different categories: sturdy ricottas and creamy ricottas. The most affordable ricottas, the kind you buy in a plastic tub, are made by large-scale producers. These cheeses are sturdy and relatively dense, and their texture is rough and grainy because they’ve been produced using machines, which break up the delicate curd. “The more you mess with the curd, the grainier and tougher it’s going to get,” says Callahan. These cheeses are best for dishes like hearty lasagnas, where their sturdiness is useful for between the layers of pasta and tomato sauce but their grainy texture isn’t going to affect the end quality of the dish.

The other style of ricotta commonly sold in the US, sometimes labeled with the term “artisanal,” is a fluffier, more cloud-like version of the cheese, often made by smoothing the cheese to remove the graininess. Sometimes cheesemakers also add a little whey or cream to add moisture back into the curd. These cheeses are more texturally pleasing, but they no longer have a particularly firm structure. If you use these this style to fill ravioli, the filling is likely to squirt out of the noodles when you cut it with your fork. They are best used as light base for cannolli filling and other sweets, to make very light gnocchi, or in dishes where the cheese doesn’t need much structure, like ricotta toast.

Some small producers also make ricottas that have their own unique qualities. Callahan, for instance, uses a different process for Bellwether Farms’ cows’ milk and sheep’s milk ricottas: While most ricotta makers use an acid of some kind to acidify their milk, Callahan cultures his milk instead. “We were lucky that we started with sheep’s milk ricotta,” he says. “With sheep’s milk, if you’re making a whey ricotta, you don’t have to use any vinegar. Sheep’s milk has enough whey protein that if you get to a temperature range in the 180s, ricotta forms. I thought maybe we could do something similar with whole milk ricotta.”

His solution is to culture the milk before making the cheese and ripen it, so that it’s already acidified before he heats it and separates naturally. Once the curds start to form, Callahan preserves their delicate texture by scooping them into draining baskets by hand. The finished ricotta is sturdy but also creamy and can be used like either of the styles above or eaten on its own, spread onto crackers or served in a bowl with fresh fruit, like a thick yogurt.

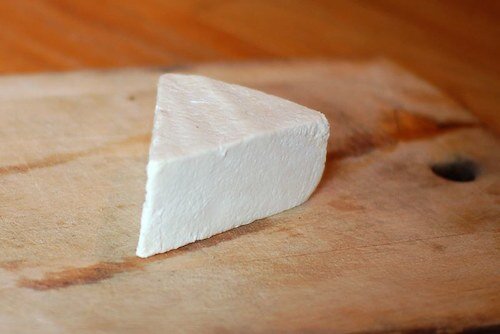

What About Ricotta Salata?

"Ricotta Salata" by ulterior epicure is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Ricotta salata is the mature version of fresh ricotta. To make this cheese, producers add salt to fresh ricotta (“salata” means salted), form it into a small wheel, then drain out much more of the moisture and age the cheese for several months. The result is dense, firm, and crumbly, with a slightly chalky texture and a salty flavor, like a drier version of feta. Ricotta salata is often used to add a bit of salty flavor and a touch of creaminess to finished dishes: It is extremely versatile and can be grated onto pasta, added to salads, or even crumbled into tacos as a substitute for Mexican cotija.